Simplified data entry: Tk::DateEntry and Tk::PathEntry

The Tk::DateEntry and the Tk::PathEntry widgets simplify the input of

structured data (namely dates and file paths, respectively), by

providing a display of valid input and allowing the user to

select from them.

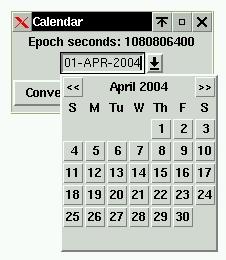

The DateEntry widget displays a text

input field with an adjacent button. Clicking the button

displays a calendar in a drop down menu, and selecting a date using

the mouse enters the corresponding string into the text input

field.

Figure 3. The DateEntry widget

Listing 3 shows the code associated with this example. Selecting

Convert calculates the number of

seconds since the beginning of the Unix epoch and displays them

in the Label widget atop the text

input field.

|

Date input is hard because there are so many ways to represent

the same date in string form. The DateEntry provides three standard date

formats (MM/DD/YYYY, YYYY/MM/DD, and DD/MM/YYYY), which can be

selected using the -dateformat

option. If a different date format is desired, the programmer

has to provide the conversion routines explicitly, using the

callbacks -parsecmd and -formatcmd. In the example above, we use a

custom date format, displaying months using 3-letter

acronyms. When parsing the input string into its numerical

constituents, we use the hash %idx_for_mon, which holds the numerical

index of each month (1..12) given its acronym. When a user

selects a date from the drop down menu, it has to be formatted

into the corresponding string, requiring the opposite lookup,

namely the acronym given the index. We build up such a data

structure on the fly in the format

routine, using the reverse

command. Since this command expects an array, the original hash

is unwound into an array in such a way that the values follow

their respective keys in the array. This array is then reversed

(so that now the former keys follow their values) and transformed

back into a hash. This trick works here, because both keys and

values are unique (again, for more information on this, see

Learning Perl, which is listed in Resources).

The convert function takes the

variable containing the input string, as well as a reference to

the Label widget as parameters, so

that it can change the value shown by the Label. Here, we do not pass a reference to

the callback and the values of the parameters in an anonymous

array to the -command attribute;

instead, we invoke the callback function directly, from

within an anonymous subroutine (a closure). The reason has

to

do with variable scoping; see the Sidebar for a

full

explanation.

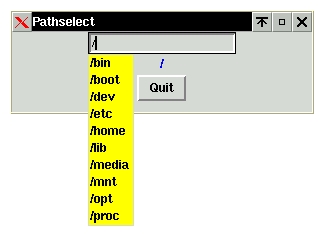

Finally, the Tk::PathEntry widget is

very simple: it provides a text input field for path names -- but

with a twist! Similar to the behavior of tcsh or the Emacs mini-buffer, pressing the

Tab key will complete the contents of

the input field as far as possible, and will pop up a list box

of possible choices if the current contents cannot be completed

unambiguously. Bizarrely, the color of the list box cannot be

changed -- unless one wants to edit the code of the underlying

Perl module.

Figure 4. The PathEntry widget

|

What makes PathEntry so interesting is

that it is

merely a widget, and not a dialog box. It can (in fact, it has to)

be combined with other widgets in a program. Therefore, it

provides a very lightweight way to add file selection capabilities

to an application.

Conclusion

These are just a few of the more "advanced" widgets for the Perl/Tk GUI toolkit that allow developers to create richer, more powerful user interfaces using Perl. All the widgets discussed here are freely available as user contributions from CPAN.

View Using advanced widgets in Perl/Tk Discussion

Page: 1 2 3 Next Page: Resources